By Elizabeth Archerd

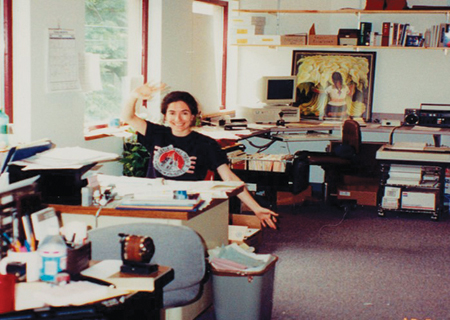

In November 2016, the Wedge said goodbye to its longest-serving employee. Elka Malkis retired as Director of Finance after working for the co-op for thirty-seven years.

In November 2016, the Wedge said goodbye to its longest-serving employee. Elka Malkis retired as Director of Finance after working for the co-op for thirty-seven years.

In June 1979, Elka was hired for a temporary summer storekeepercashier job, during a group interview by all 20 or so “coordinators” in the worker collective. The interview took place in a coordinator’s apartment. Elka and two other candidates sat on the floor surrounded by seated and standing staff, though one interviewer did yoga in a corner.

The co-op had just moved from the original basement shop on Franklin to a 7-11 on Lyndale, and business was robust. Sales were expected to drop in autumn. They didn’t and Elka stayed, but no one mentioned that she was no longer a temp. Within a year, her duties included preparing daily deposits, “because I wasn’t afraid of numbers,” she quipped. She later moved to Produce—a super, fun job in an all-female department that was both a feminist breakthrough and a daily artistic experience. It was rare at the time for any women in grocery to work with produce, but co-ops did not stand on such traditions. Even back then, the reputation for gorgeous produce was a huge draw to The Wedge, and not just for natural foods or co-op enthusiasts. Produce, aka The Wedgetables, had a truck and buyers purchased daily at local warehouses and the Minneapolis Farmers Market. When they returned to the co-op, the food was immediately moved into the store coolers. The women were proud of their strength and the beauty of their displays. Whatever was most beautiful—deep purple eggplant, brilliant white cauliflower, vibrant red peppers—became the center of the display.

Few co-op workers had backgrounds in business, so systems were developed by experiment and argument. Business decisions about vendors, new products, major policies, and minor procedures involved near-Talmudic discussions about health, ethical, environmental, and social implications of the topic at hand. One example: coordinators all earned the same hourly wage, but parents received more health care reimbursement money than non-parents. Eventually someone pointed out that she supported college loans instead of children, and why should she get less compensation for the same work? As in so many decisions, there was tension between the ideals of equality and fairness.

Food co-ops were deeply community-based, with workers and members from diverse class, ethnic, and educational backgrounds, including immigrants, elders, and veterans. A strong sense of responsibility lay behind formal and informal practices. Workers even kept the store open on Thanksgiving and Christmas out of the service ethic.

The co-op acted as informal financial guardian for Jack “The Runner,” a disabled Vietnam vet who wore only swimming trunks year-round and regularly did push-ups on the co-op parking lot. He cashed his disability checks, put the money in a bush (no pockets), and it always went missing. When a co-op worker found that out, the collective began storing the cash in the office safe for him. Elderly Russian immigrants came in frequently for “seconds” produce, sold for a dime/pound. One such regular, who occasionally brought in rugelach for staff, once stuck her thumb deep into an eggplant, held it aloft proclaiming “Is garbage, garbage! Ten cents!” Give and take with whoever showed up was part of the job.

Elka’s Russian Communist grandparents, who organized co-ops and labor unions after immigrating to the U.S., had influenced her to be pretty leftist. She was surprised, therefore, to realize that the collective was becoming highly ineffective as the co-op grew. Most workers didn’t attend meetings yet resisted decisions made in their absence. Frustrated because of the unmet need for effective management, she instigated the Voting Collective (VC). Coordinators committed to attend meetings while those who did not agreed to abide by the decisions, and VC membership re-opened every six months. Nothing changed, so in 1981 the VC petitioned the board to install management.

Elka’s Russian Communist grandparents, who organized co-ops and labor unions after immigrating to the U.S., had influenced her to be pretty leftist. She was surprised, therefore, to realize that the collective was becoming highly ineffective as the co-op grew. Most workers didn’t attend meetings yet resisted decisions made in their absence. Frustrated because of the unmet need for effective management, she instigated the Voting Collective (VC). Coordinators committed to attend meetings while those who did not agreed to abide by the decisions, and VC membership re-opened every six months. Nothing changed, so in 1981 the VC petitioned the board to install management.

Many people, including Elka in the early days, assumed that being a co-op meant being against growth and profit. Was there a way to achieve stasis, a balance where the co-op would be able to continue to improve wages and infrastructure without growing? She realized that co-ops exist in neither a vacuum nor in a cooperative economy. Ideology gave way to a deeper understanding of cooperative principles (profit belongs to the members, growth means more members to serve and more organic producers to support) as well as the reality within which coops function.

In 1985, Elka left the co-op to start a record company, but shortly thereafter she returned to become the bookkeeper’s assistant and then the bookkeeper. Like many people in co-ops around the country, she was largely self-taught. As the Wedge approached each growth cusp that required more financial sophistication, she turned to peers in the local and national co-op community, who readily shared their experience.

Working with a generous community of cooperators who wanted to help each other was a joy. Eventually it was her turn to be the expert for co-ops on their way up, and she happily engaged them. “It never occurred to me not to help. Why wouldn’t I help?” Instead of holding on to some corporate “competitive edge,” cooperators practiced a “cooperative edge,” sharing what they had learned and encouraging each other. Collaboration and creativity ruled both inside the Wedge, where managers are a true team, and at the national level.

Working with a generous community of cooperators who wanted to help each other was a joy. Eventually it was her turn to be the expert for co-ops on their way up, and she happily engaged them. “It never occurred to me not to help. Why wouldn’t I help?” Instead of holding on to some corporate “competitive edge,” cooperators practiced a “cooperative edge,” sharing what they had learned and encouraging each other. Collaboration and creativity ruled both inside the Wedge, where managers are a true team, and at the national level.

Elka did not join the Wedge to have a career, but she knew about natural food and enjoyed the “hubble-bubble” of retail. She started as a temporary storekeeper-cashier and ended as the Finance Director of one of the most successful food co-ops in the U.S. She said of her time, “I found a home, I didn’t just find a job. I found so much support; so many friends; so many amazing, brilliant, smart, committed, caring people in the coop world. I am so lucky. I am so lucky that I fell into that.”

Elizabeth Archerd, former editor of the predecessor of The Share, worked at the Wedge with Elka Malkis from 1981 to 2014. It was one of the pleasures of her career.

Back to the Winter Share articles